70% of new users churn before ever engaging with the app’s core features. Businesses pay for acquisition without getting a chance to demonstrate the product’s worth. Ironically, the app itself may be valuable, but bad onboarding prevents users from experiencing its benefits.

Rubyroid Labs, experts in UX design services, examine why users drop off and how early abandonment affects product profitability. We also share principles of onboarding flow design that shorten the path to value and give users a reason to stay.

Contents

- Why do users drop off at onboarding?

- How does this affect your business?

- Do you always need onboarding?

- How to design onboarding screens

- Onboarding optimization checklist

- Conclusion

Why do users drop off at onboarding?

The bridge between user frustration and a successful first impression comes down to what product designers call the 60-second rule. This rule dictates that the core value proposition must be felt before the first minute expires.

Users arrive with limited attention resources and specific expectations. Thus, the designer’s goal is to align the interface with the following psychological realities.

Unresolved cognitive loops increase abandonment

The Zeigarnik Effect posits that people remember uncompleted or interrupted tasks better than those that have been completed. It can actually be the primary driver of abandonment if not balanced correctly.

The correlation lies in cognitive tension. When a user starts an onboarding journey, they open a “mental loop”. The brain creates task-specific tension to keep the details accessible in short-term memory. This tension makes a user want to fill a progress bar from 90% to 100%.

If the user is interrupted by a paywall or a “hidden” step they didn’t anticipate, that tension becomes cognitive load. Users hate “surprise” tasks. If they are about to finish but then hit a “Wait, one more thing!” screen, the Zeigarnik Effect is reset.

To find relief from this mental pressure, the user may simply “close the app” to force the loop shut.

The absence of an early value moment leads to early drop-off

The Peak-End Rule holds that we evaluate past experiences almost entirely based on how they felt at their peak and at their end, not on the sum of every moment.

The “peak” must occur within the first minute. This is the “activation moment” where the user realizes the potential value. For Spotify, this is playing the first song; for a productivity app, it is successfully creating the first list item.

Identifying these activation moments often requires a deep dive into user behavior. You can learn more about this in our guide on Data-driven UI design.

If the first minute contains only forms, permissions and no value, the “peak” is negative, and the user’s memory of the app will be permanently tainted. They most likely won’t return.

Perceived distance from the goal reduces user motivation

The Goal Gradient Effect is another reason why interest fades during the onboarding user experience process. Behavioral science indicates that effort increases as the user approaches the goal.

In the first 60 seconds, the “goal” must appear imminent. If the user feels they are “miles away” from the value, the motivation gradient flattens, and abandonment spikes.

How does this affect your business?

Analysis of current market data indicates that the average mobile application loses between 70% and 80% of its daily active users within the first 3 days.

This implies that for every 100 users acquired through marketing spend, roughly 75 are lost immediately after the first impression. By Day 30, this number typically plummets to single digits, often between 2% and 6%.

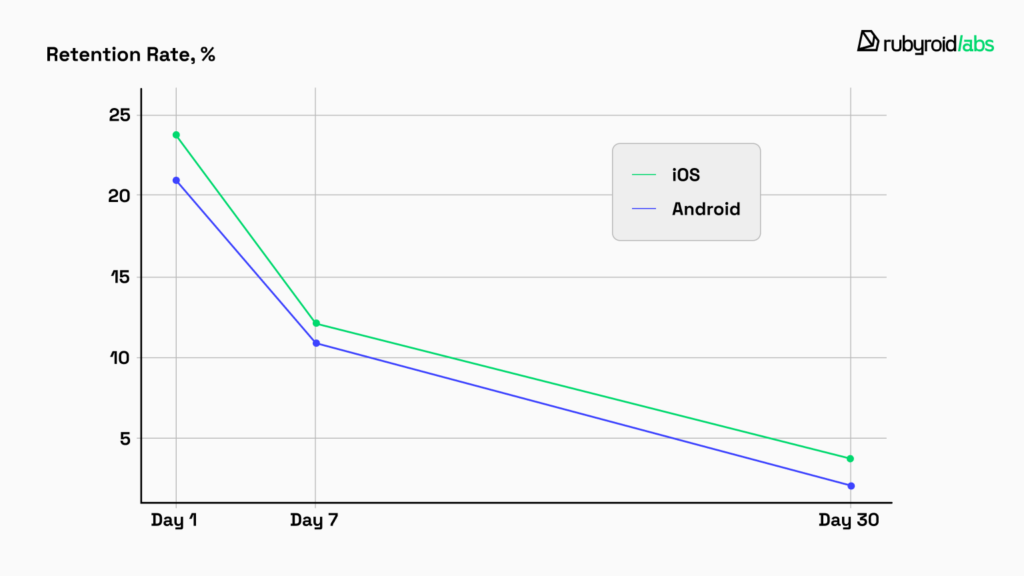

The table below illustrates the retention disparity between iOS and Android and the steep decline from Day 1 to Day 30.

| Android retention rate | iOS retention rate | Note | |

Day 1 | ~21.1% – 23.0% | ~23.9% – 25.6% | iOS users show slightly higher initial stickiness, potentially due to higher device uniformity and UX consistency. However, losing ~75% of users immediately is the industry norm. |

| Day 7 | ~11.0% | ~12.0% | The “activation gap” widens. Users who did not find value in the first week are permanently lost. |

| Day 30 | ~2.1% – 2.6% | ~3.7% – 4.1% | Long-term retention is negligible if the first 60 seconds did not establish a habit loop. A Day 30 retention of >10% is considered elite. |

In software, you pay a high price to acquire a user, hoping to earn that investment back over time. Frictionless onboarding design bridges this costly entry and future value.

If a user stumbles in the first 60 seconds, the bridge collapses. Your Customer Acquisition Cost sinks without a trace, and the potential Customer Lifetime Value is lost.

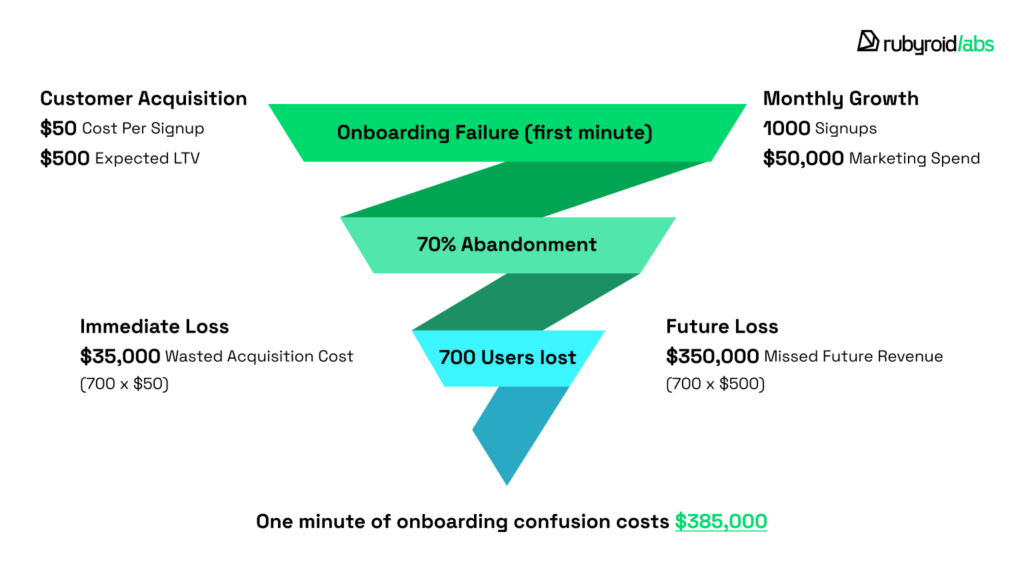

Let’s take an average B2B application where you spend $50 in marketing to acquire a single customer with the expectation that it will generate $500 over their lifetime.

If you drive 1,000 signups in a month, you have essentially “bet” $50,000 up front. If your onboarding design fails and 70% of those users abandon the app within the first minute, you lose the $35,000 spent acquiring those 700 lost users and forfeit $350,000 in potential future revenue.

In this scenario, a minute of confusion costs the business over a third of a million dollars.

However, the financial impact of onboarding design failure is not limited to the loss of a user.

- It causes significant damage to the brand. Over 52% of consumers state they are less likely to engage with a brand after a poor mobile app experience. A user who deletes the app becomes a detractor and may actively discourage others from installing it.

- It increases customer support burden. Users who are confused within the first minute but do attempt to stay generate support tickets. Their queries increase the operational cost to serve (CTS). Password-related onboarding friction alone accounts for 40-80% of help desk costs in many organizations.

Does industry type play a role?

Yes, it does. The “60-second onboarding rule” applies differently across verticals.

For instance, news and information apps enjoy the highest retention rates. Their value proposition is information retrieval, which is immediate and requires low cognitive input. The user opens the app, sees a headline, and the “value” is delivered.

Similarly, higher-than-average Day 1 retention is seen in the fintech and finance sectors (approx. 30.3%). We see this variance firsthand when building Custom CRM solutions. The user’s motivation is high, which overrides some friction. However, this is not an excuse for poor design.

Games maintain high Day 1 retention (~28-33%) because they masterfully utilize interactive onboarding, throwing the user into Level 1. It becomes an integral part of the game itself.

By contrast, the user’s patience is shortest with travel apps. This phenomenon stems from the transaction-oriented journey of travel planning. When the user interface fails to facilitate the core objectives swiftly, user retention plummets.

Do you always need onboarding?

The more products we observe in real use, the clearer one thing becomes: onboarding is not inherently valuable.

At its core, onboarding is a set of flows and UI elements that help users get familiar with an interface and complete the initial setup.

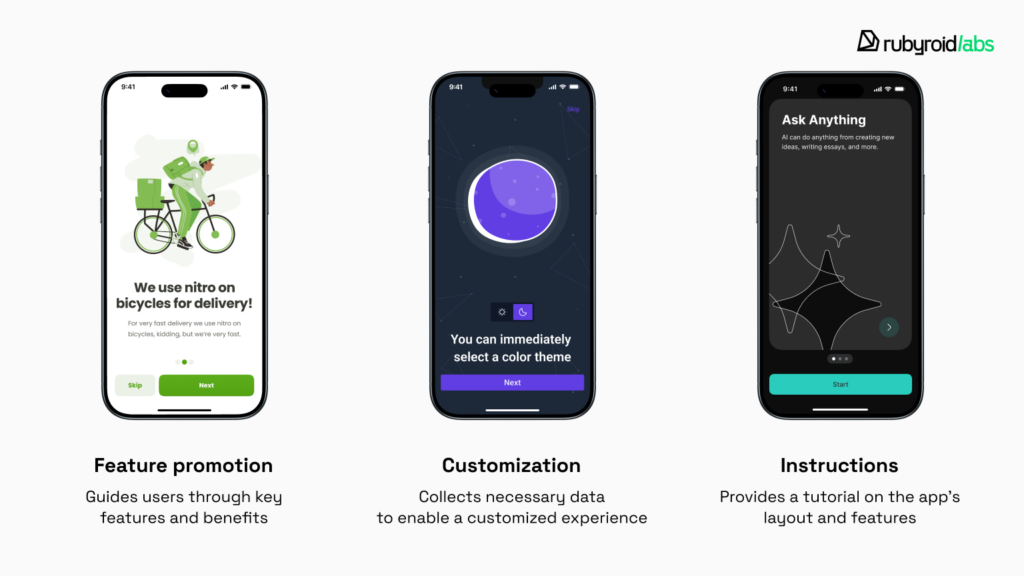

It’s built from three components, used separately or in combination.

Feature promotion introduces what the product can do. This often drifts toward marketing rather than guidance. Users rarely install an app without a purpose, so front-loading them with feature lists tends to be ignored.

Feature onboarding makes more sense later, when something truly new becomes available and actionable for an existing user.

Customization requires user data. Certain inputs (like selecting a language in a learning app or creating an account in a banking product) are essential. Most other requests, however, are misplaced.

It’s difficult for users to decide on visual preferences before they’ve even used the product. It’s better to leave sensible defaults and offer customization later.

Instructions aim to teach users how to use the interface. These range from swipeable tutorials to overlays and interactive walkthroughs.

When instructions exist to compensate for unclear design, they don’t solve the real problem. When they support genuinely novel workflows, they can be useful if they are brief, optional, and tightly focused.

Onboarding is not limited to the first app launch. It can reappear later, for example when a major redesign ships or when new functionality introduces behavior users have never seen before.

Don’t interrupt users upfront, guide them at the moment the feature becomes relevant. This approach respects the user’s existing mental model and avoids forcing them to remember information they may not need right away.

When onboarding does more harm than good

Every extra screen increases interaction effort. Even skipping onboarding requires action.

The traditional approach assumes users will remember what they are told. However research consistently shows that memory is limited, especially when information is presented out of context.

Studies by Nielsen Norman Group highlight another issue.

In quantitative usability testing of mobile apps that relied on deck-of-cards tutorials, users who read the tutorials were no more successful at completing tasks than those who skipped them. Success rates were nearly identical. Task completion times showed no meaningful improvement either.

What did change was perception. Participants who read tutorials rated the same tasks as more difficult than those who did not. Tutorials made simple apps feel more complex than they actually were.

This effect matters. Promising intuition but starting with a tutorial creates instant distrust. It suggests the product is more complicated than advertised.

So, when is onboarding worth it?

It earns its place in a few specific scenarios:

This is particularly true for complex Enterprise UX/UI design, where specialized tools require a higher level of guided discovery.

Even then, onboarding should be treated as a last resort.

Before designing new flows, test the product without them. If users struggle, the first question should not be how to explain the interface, but how to simplify it.

The most effective onboarding often barely looks like onboarding at all. Interactive walkthroughs work, but only if they feel like a short practice.

The takeaway is not that onboarding design is obsolete. It is that it’s expensive. In many cases, the same resources deliver more value when invested in clearer layouts and interfaces that explain themselves through use.

How to design onboarding screens

As we’ve seen, users abandon products that delay value and engage with those that demonstrate immediate utility.

So, if you still need onboarding, let’s now explore how to design for that crucial moment of first value.

Deliver a tangible win before requesting anything in return

People want evidence before they invest effort or personal data. Remove high-friction requests (credit card details, enabling notifications, email verification, etc.) until after the user has experienced the core benefit. Let users interact with real functionality.

Ask for commitment only after the product has earned it.

Duolingo successfully uses this gold standard because it allows using the product before creating an account.

Upon opening the app, you are not asked for an email or password. You are asked, “What language do you want to learn?”. Only after the user has completed a lesson and feels a sense of accomplishment does Duolingo ask them to create a profile to “save their progress”.

Users have already invested effort and gained a win, so they are much more likely to “pay” with their data to keep it.

The “Netflix exception”

Netflix is a “negative” example of activation design because it does the opposite of the advice above: it forces account creation and payment before letting you see or use the product. You cannot browse the library or watch a trailer without signing up first.

This lack of transparency forces users to guess the service’s value. But why doesn’t this kill their success?

- Users landing on Netflix don’t need to be convinced that the product is valuable. Marketing has already done the onboarding for them. They arrive with high intent.

- Netflix is not a tool you have to learn how to use. The “learning curve” is zero.

You can only break this rule if your brand is so powerful that the user’s desire to get in is stronger than the friction you put in their way. For 99% of products, copying Netflix’s “paywall first” onboarding is a death sentence.

Show progress

Designers can leverage the cognitive tension of starting a task by visualizing the onboarding as a checklist or a progress bar.

For instance, by showing a progress bar that is partially filled, the interface creates a psychological need to “close the loop”. The user feels an urge to reach 100%.

This can be combined with the Endowed Progress Effect, where the user is given a “head start”. For example, the act of signing up counts as “Step 1” and verifying email as “Step 2”, so the user enters the flow already 50% complete.

This artificial proximity to the goal makes the remaining effort seem smaller. Motivation increases when the finish line feels close.

When a new user lands on their profile in LinkedIn, the meter is never empty. The simple act of signing up and stating your job title gives you “Beginner” status, with the progress bar already partially filled.

Rather than asking users to input all their data at once, LinkedIn’s progress bar breaks the task down, suggesting a single next step to upgrade their status (e.g., “Add a photo to reach Intermediate”).

Progress indicators should be persistent and honest, without surprise steps. For multi-step flows, keep progress visible at all times.

Limit choice

If the first screen presents three different subscription tiers and a request for push notification permissions, the cognitive load exceeds the user’s “budget”.

Narrow the path to a small set of meaningful decisions and defer the rest. Advanced options can wait until users have reached their first success.

For example, Pinterest strictly limits the user’s options during onboarding. The user is presented with a grid of topics and has only one choice: tap 5 topics they like.

Pinterest doesn’t ask the user to type keywords (high effort). They ask the user to recognize and tap images (low effort). They don’t explain how to “Pin” or how to “Create a Board” yet. They hide those features until the user has completed the interest selection and generated their first personalized feed.

Onboarding is not the place to showcase everything the product can do. Highlight only the features that lead to the activation moment.

Ask less and do it politely

Request only what is essential for the product to deliver value. Everything else can wait.

When asking for sensitive data (e.g., location, contacts, or phone number), onboarding microcopy must explain why it is needed.

Explaining the reason feels cooperative. Users are far more willing to share information when the purpose is explicit.

Remember that large forms and early preference screens delay the peak moment described by the Peak-End Rule.

Implement smarter authentication

Have you noticed how much easier and faster it has become to register or log in somewhere compared to 7-10 years ago?

Back then, you had to create a username and a password (which had to meet specific, often overly complex, format requirements). If you forgot your password, you faced a lengthy recovery process.

Today, authentication has become much simpler and quicker. Many services have replaced traditional passwords with biometrics, one-time passwords, and social login options. These details are part of a well-thought-out UX.

In the US, fingerprint and face authentication are now widely trusted. In China, QR-code login is a common alternative that removes passwords entirely.

The less a user has to remember or type, the smoother the experience feels. Onboarding should never be a memory test. Our Ruby on Rails development team focuses on implementing these passwordless flows to ensure the highest security with the lowest possible user friction.

Use instructions only when behavior is truly new

Instruction works best when it is contextual and triggered by user intent.

Guidance should appear when the user attempts a specific action. These “pull” moments align with how people learn. They seek help when they need it.

Contextual tips, coach marks, and short walkthroughs should be easy to dismiss and easy to find again.

Design empty states as invitations to act

Well-designed empty states should never be truly “empty”. Use the space to show examples, suggest quick actions, or explain the benefit of taking the first step without relying on separate tutorials.

Effective onboarding design highlights only what is necessary for the user’s immediate goal and hides the rest. Once users succeed at something meaningful, curiosity takes over.

Every screen should be evaluated against: does this bring the user closer to value? If the answer is no, it does not belong in the first minute.

The most effective onboarding feels like a natural beginning. When users barely notice it, but reach value quickly, the design has done its job.

Onboarding optimization checklist

To determine if your current onboarding needs a redesign, we’ve prepared a list of questions for you to answer.

If your app fails:

- 1–2 checks → Targeted UX fixes may be sufficient.

- 3–4 checks → A UX audit is strongly recommended. For those in the retail space, we have a specialized guide on how to conduct a UI/UX audit for e-commerce.

- 5 or more checks → A redesign is mandatory.

Conclusion

Users abandon onboarding when:

- unexpected tasks break their sense of progress;

- no early value moment appears;

- the goal feels distant rather than within reach.

When teams turn to onboarding, they usually rely on one or more familiar components: feature promotion, customization, instructions.

None of them is inherently valuable. Feature promotion too early drifts into marketing. Customization before use forces premature decisions. Tutorials have been shown to make simple apps feel more complex than they actually are. Guidance works only when it is contextual, optional, and triggered by intent.

The strongest insight from all of this is: a good designer’s primary responsibility is not to explain the interface, but to reduce the need for explanation.

This is the principle that guides our design work at Rubyroid Labs. We don’t measure success by the number of onboarding screens shipped, but by how quickly users reach their first meaningful outcome.